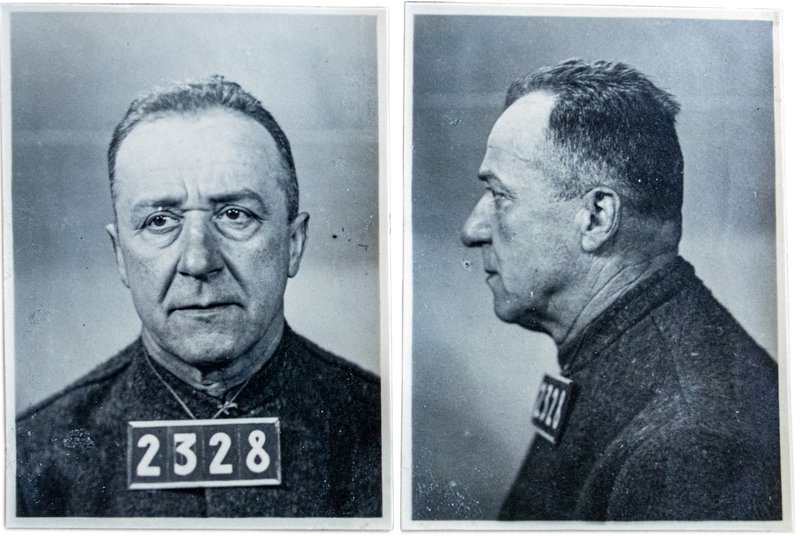

An eerie mugshot displaying the hollow-eyed visage of an incarcerated helmsman in prison attire waited 63 years at the Národní archiv in Czechoslovakia to be discovered.

Puzzling together the chronology proves to be a bit of a challenge, as the photo of his granddaughter’s first school day in Vienna turns up in a cigar box with old family relics. Did Stjepan move to Austria straight after being released in a spy exchange between Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia? Later in life, Milica wouldn’t retain the German language, nor could she remember why she was sent off to live with her grandparents in a foreign country. Perhaps a clue might be found in a yellowed photo from the Adriatic that recalls the memory of summer 1987 when her son, Robert, joins his grandparents at a resort for war invalids in Montenegro.

Playing with the relationships between image and knowledge and past events and their documentation, photographs from personal and public archives are reframed and reimagined. Remembrance and fanciful reveries delineate the past as part of a personal and interpretive claim on history, in this case, postwar Yugoslavia. Throughout the stories, the mysterious number 5 reappears.

In November 1953 Stjepan Antešić was sentenced by the Krajská prokuratúra (District Attorney) in Nitra, Czechoslovakia, to twelve years in prison as a spy from a foreign power. Mugshot from the Národní archiv, Prague.

Komarno 1953

Stjepan had been warned by his friends, the Hungarian-speaking Kertész family from Komarno on the eastern bank of the river, that the secret police would be waiting for him should he leave the barge. Sooner or later, however, a captain needs to feel the terra firma beneath his feet, and the instant Stjepan set foot on Czechoslovak soil, they nabbed him.

He was casually dressed and sported a black beret. The poplars had spread their first light-green boughs when he was taken by car to the Prosecutor’s Office in the regional capital Nitra in the Danubian Lowland.

The interrogations were harsh, and following the verdict, he was moved to the infamous Leopoldov Prison, whose dank corridors and underground bunkers were well suited for the protracted torture of an enemy of the state. His disappearance lasted three years.

We will never know how it came to be that Stjepan, a convicted terrorist and national traitor in a foreign land, was set free in a furtive spy exchange in 1959. He was secretive about his time serving as a Yugoslavian agent. Only when his daughter’s own daughter was to marry did he choose to confide in his future grandson-in-law.

Whatever horrific stories and testimonies were confidentially shared between these two mariners, we can only imagine. Stjepan passed away at an advanced age and his daughter’s son-in-law died soon after, and all too soon. The passage of time between the one’s death and the other’s was too brief to compromise trust, so not a single word on the secret life of the agent was ever uttered. What remained was a facedown card. Collateral for a fate whose backside was facing the world.

We carry these fates—with or without black berets and laced-up shoes—like an ace up our sleeve. In the breast pocket near our heart—like a Little Red Book. And when the time comes to show your cards on the table, it is too often too late. Nobody knows anymore the value of the facedown card.

But we do know one thing no one else knows. Something that does not appear in the yellowed documents in Prague’s post-war archives. We know that Stjepan held a specific phobia of anything that was five in number.

Some days (might it have been five?) prior to the arrest, he discovered that five pages were missing from the copy of The Count of Montecristo he carried with him. Someone had torn out the pages as if they were five disheveled strands of hair in a bushy brow. The night before his arrest, during the first watch and the fifth bell, he noticed five green-headed ducks, among them not a single female, languidly bobbing by the stern. The birds flitted beside the algae-encrusted hull before catching some gentle river currents under the moonlight. Perhaps these purely numerical apparitions were nothing to get hung up over? He had already read the dog-eared copy of Alexandre Dumas' tale, now devoid of its five opening pages (in which the Count has not yet been deceived by his tormenters). And a flock of five was nothing more than a haphazard line-up from the countless carefree ducks that paddled along the muddy banks of the Danube. The real portent was this: Precisely five people knew of his location—and none were family members. Five of everything. Five apple cores, five bottle tops from long-drunk bottles of beer. Five random thoughts reminding him of his wife, his only daughter, her growing family, their apartment in Belgrade and the old house on the island that was now so distant. Five days of uncertainty and evasive glances in court. Five blows to the head with brass knuckles. A rat and her five pups shrieking at night. And finally, the five men seated at the table with an unmarked deck of cards.

In the dream—or through the foggy eye of hypnagogia—they turn up time and again, all five. Each one identical to the next. They might be screws, or even sharply dressed jailbirds, the five who relentlessly bet down to their skin (since the pot contains no gold).

“Well, that’s me”, she would explain to the befuddled inquirers. “My first day in school”. The photograph of Milica Brečević, née Vujisić, was taken by an unknown photographer in Vienna, in 1959. She couldn't remember, but chances are that her grandfather Stjepan Antešić was the phantom behind the camera.

Vienna 1959

We can all reasonably agree that the first day of school is a rite de passage. And to top it off, if this initiation is staged in a foreign land, if it involves meeting hordes of children with unfamiliar names, whose critical eyes will measure you from top to toe—and if, above all, you get the question: Wie heißt du? in a language you do not understand a shred of… Well then, the initiation is assuredly of equal rank to being hung by hooks in a rainforest amid the deafening squawks of hundreds of colorful macaws and wondering if you will ever get out alive.

The child as outsider—trespasser even—is a well-known motif, but the shame of this exclusion seldom appears as palpable as in this scenario. She is seven years old, and she is standing at the top of a staircase. With head tilted and eyes downcast, she holds on tightly, with both hands, to the handle of her schoolbag, a leather briefcase.

Her thick socks have slid down. Her laced boots point straight forward, and she hides in plain sight—ensconced not only from the one taking or viewing this picture, but from the whole world and for all future. Below her, the city offers constant motion, an unrehearsed play with five protagonists: a woman in a pale hat sauntering down the middle of a cobbled street, the dainty feet of elegant ladies sweeping up and down the steps, the strides of a tieless man eagerly swinging his arms for momentum up the steep steps. Only the little girl and two cars with the rounded shapes of the ‘50s stand still in this Viennese alley.

It has been decided that she will live with her grandparents until further notice. The Danube is the bond that connects her birthplace Belgrade with Vienna, where Grandpa Stjepan has now been stationed. His wish was to take someone from his family with him to this foreign land—at least, that’s how she remembers it. This river boat captain (cum harbor pilot) has the one child. Daughter Dorica is the apple of his eye, and she would often accompany her father on the flat barges that slowly float through cities such as Novi Sad, Komárno and Budapest. Now that she has formed a family of her own, she can probably spare one of her two children for a time.

The little girl does not personally remember how she got to Vienna, but one thing is certain: It must have been overland, since the river link between Belgrade and Vienna crossed the Iron Curtain, countries that Stjepan for obvious reasons would never again set foot in. At primary school, she is put in second grade without knowing a word of German, let alone Austrian German. Little by little, she learns the lingo, initially from the Austrianisms (unlike Germanisms) that are cognates of her native tongue: palatschinke, karfiol, fisolen – palačinke, karfiol, fažol. A few years later, back in Belgrade, she will have to work off her German accent.

Great-grandfather has retired and his son-in-law wants eventually to obtain a home for his family. As guarantor for the apartment credit, Stjepan stipulates that his daughter Dorica’s name must also be on the contract. This is too much to ask of a son-in-law. Does the geezer presume the right to make such demands on him—a grown man? Gojko marches into the freshly opened Swedish employment service in Belgrade and signs a contract for a job at the Volvo automotive plant in Gothenburg. Then off once again, this time with Mom, Pop and big brother. She begins her first year of the gymnasium in Sweden where she will once again be asked Vad heter du? in a language she knows diddly of.

She does not recall all the journeys. There have been many. Stjepan was among the first to secure travel documents abroad in the late fifties in a country smack in the middle of a global clinch between West and East. When she marries in Sweden at the age of twenty, it is with a seaman from her motherland. Her husband traverses the great oceans. As returning Gastarbeiter, they cruise thousands of Autobahn kilometers every year in newly purchased cars, while smuggling TVs and unroasted coffee in one direction, rakija in the other.

Still, it is the far earlier journey that remains as a flashbulb memory. For there is a certain something about how a dusky landscape rushes past a train window. The thumping sound is boomy, but it provides the same heart’s ease as the creak of a cradle rocked by a hand as even and constant as the lengths between railway sections. The toilet door has not been properly shut and slams with the lean of the train—but not even this irregular clatter can undermine the assurance that everything is growing dark and that the world will soon be engulfed by the night. In the teetering corridor stands a man with a well-groomed moustache, two black lines over tight lips. He has rolled up the sleeves of his freshly ironed white shirt and leans out through the window. His gaze is dreamy, distant and yet present. Slavonia's flat expanses of endless arable land and the dim silhouettes of trees and buildings sweep past his total lack of attention. He draws a deep puff from his cigarette and blows out smoke, as the brakes squeal and grate in the soft bend. He looks like a man who has lost everything but won just as much.

In the compartment, four men in similar white shirts are visible (she could even swear that they all had matching moustaches). They play cards off a folded-out trunk on which they have set a spread of cold cuts and schnapps poured into unexpectedly elegant crystal glasses. After each round of play, they let fly hoots and howls and then gang up against one player who suffers five crisp blows to the head with what appears to be a huge turnip, complete with tops and soil. They count out loud: one, two… five. At first, she has not noticed that the man by the train window is now facing her. He smiles without showing his teeth, then flicks the cigarette, whose ember flies out in sparks over a recently plowed field. The odor of moist soil is mixed with smoke, sweat and dried urine from the toilet in which missing the target is a sure bet. The man closes the window, enters the compartment and shuts himself in.

Milica simply does not remember whether she was on her way home or if the train was taking her to Grandpa in Vienna. Or could it be that she would stay in Zagreb with Aunt Danica, whose husband was a flight captain and always wore a stately uniform with epaulettes and all? But one thing is for sure: this was when she resolved that, when she grows up, she would take up smoking.

The young man in this photo from 1987 has returned from a sojourn at a health resort with his grandparents, Dorica and Gojko (to the right). A residence that has been revealing, to say the least.

Igalo 1987

It looks like any Montenegrin coastal town. Barren, windswept mountains in the background, scattered houses with brick-red roofs, a church on a ledge and then the vast sandy shore. Grandpa Gojko was incredibly proud that it was all inclusive: the train journey from Belgrade (although in a second-class smokers’ compartment), three meals a day plus dessert and various full-body treatments, such as sports massage and foot care. His grandson looked particularly forward to Dr. Oetker's powdered pudding in three different color and flavor combinations: yellow vanilla, brown chocolate, and pale pink strawberry substitute.

The young man traveling with Grandpa Gojko and Grandma Dorica to Igalo during the sizzling summer holidays of ’87 was the only one of all the assembled guests who had not experienced the War. Nonetheless, the Sutjeska offensive, the liberation of the cities Zagreb, Sarajevo, Belgrade, zone A and zone B of Istria and environs, and references to Trieste as “our town” and other nation-building tales were likewise part of the teenager’s history.

At the first gathering in the atypically airy dining room, whose wide-open sliding doors allowed the sheer curtains to flutter in the mistral, he promptly became the favorite of ‘aunties’ and ‘uncles’ alike. Particularly delighted were these strangers in the fact that he—as a byproduct of continuous political discussions with older relatives, grandparents and their aged friends—had developed an extraordinarily well-mannered mode of conversation regarding things that were disproportionate to his modest age.

War veterans, now long in the tooth and with bushy white moustaches, have a decidedly cordial, if strict, manner that recommends an unforced socializing. Above all, these stiff-necked gents differed markedly from the young man’s grandfather, a bohemian and street-smart type. It was hard to imagine that the latter had ever been in battle. The boy grasped very well that it was through contacts, the well-connected cronies in the speakeasies lining the streets of Belgrade, and through skillful card playing into the small hours that Gojko had worked out a paid stay for himself, his wife and grandson at a rest home for the old guard.

After the last spoonful of tasty pudding, decorated in accordance with the brown-yellow-pink tricolor, the time had come—to stroll down to the sea.

The descent from the rest home up on the hill occurs in a united troop. The ‘aunts and uncles’ (and a lone teenager in yellow bathing shorts) advance leisurely, equipped with parasols, rolled-up beach mats, towels and coolers packed with cold beer in squat brown bottles bearing the green label of the brand "Nikšičko". Once the squadron finally reaches its destination—the shimmering sea that runs along the creamy fine-grained sand—uncles and aunts become like children. Sand swirls round as the folding chairs and parasols are sunk into the soft surface.

Neatly dressed elders strip off their baby-blue long-sleeved shirts, dirt-brown trousers and floral dresses. Socks are painstakingly snapped off stiff legs and folded neatly to sit atop each pile of clothes. What will forever be imprinted in the young man’s memory is the moment when the routine act of "taking off" does not stop at the clothes. Trousers, shirts and other garments are followed by body parts in the form of wooden legs and prosthetic arms in skin-colored plastic. Elastic bands are snapped, straps unhooked, casings released, revealing pale, scarred stumps of limbs left behind in the limbo of war.

The fact that every uncle has some spare part is something the young man needs a while to come to terms with. He had not noticed these insufficiencies before, but now in their unclad state, they could not be hidden. His best response is to immediately immerse himself in the sea, a setting where arms and legs have an utterly different function.

That day the adolescent boy would learn to dive really deep. Equipped with a new face mask and all the learning his cousin had shared when they speared octopi in the early summer by the cliffs outside Fažana, Istria, he takes a deep breath, lifts his legs and thrusts himself down through the pliant water. When his ears sense pain, he pinches his nose and blows. Then, crackling as his eardrums are under pressure, he propels his fins like never before. Below, a red starfish gleams, lying prone on the ribbed seabed of beige sand. One of its five arms is severed and hangs from a thin thread at a sharp angle, a fracture in this otherwise symmetrical body. A shoal of sand smelts has picked around the calamitous echinoderm; they act as a coordinated, offensive mob, taking turns nibbling at the starfish's limp arm. The boy has gathered starfish before, laid them in the sun to dry and watched as they slowly contort in a drawn-out death struggle, but he instantly feels sympathy for this cripple. He waves off the shoal before surfacing for oxygen. After several dives, he understands the hopeless nature of the enterprise: that he can do nothing but delay the inevitable fate of the hamstrung starfish.

Arising from the sea, hobbling in step with the rocking swells of the waves and exhausted after the countless dives to the bottom, the youngster has almost forgotten what drove him to the undulating, salty depths. With a mask in one hand and yellow flippers in the other, he abandons the waves for the parasoled party. The vibe on the beach is rollicking and most likely ongoing for as long as he had been away. Grandpa is sitting on a collapsible plastic chair at a table now unfolded and wedged in the sand, and he bears a grim look under his wrinkled brow. His company consists of Branimir, Grga, Aldo and another uncle, whose name the young man has forgotten. These five are playing cards.

Grandma has gone back to the hotel (which the boy now understands is a rest home) because she has her usual headache and must rest her eyes in semi-darkness. She is weary more often than not, and Mother has on occasion whispered to Father that we must understand that Dorica has weak nerves, something neither electric shocks nor other forms of therapy have managed to cure.

The young man stands by his grandfather and eyes the jovial company. On the table stands an unmarked bottle and single-shot glasses with a golden ring around each lip. Branimir pours, and they toast and throw back the liquor, looking at each other's cards with hearty laughter and remarks. They are all wearing swimming trunks. Grga is missing his right arm, Aldo his left leg from the knee down. Only Grandpa is dressed, in khaki chinos and a pale-blue short-sleeved shirt.

Grandpa’s opponents are also wearing their titovkas, a kind of boat cap with the enameled emblem of a gold-edged red star above the forehead. Grga has donned his titovka on a tilt, so ostentatiously that it seems likely to slide off his bald head at any time. It makes for an impish impression. As if the informal combination of a military cap and swimming trunks was not enough. The boy wonders why they have brought soldier caps to the beach when suddenly the elder, whose name he does not remember, fires off a juicy expletive involving everyone’s long-dead mother—then bends down, picks up a prosthetic leg and slams it on the table, upsetting one of the shot glasses whose brandy runs out in a streamlet dripping onto the sand. Annoyed, Grandpa contemplates the wasted liquor.

So, these are the stakes then! The hell with money, the devil take glory! For the elders appear to be playing for each other's spare parts! To make matters worse, it is apparently the boy's grandfather who wins the pot: two right arms, a left leg, a right foot and a white glass globe with a blue iris, rolling around on the table.